One of my favorite things about Sunday afternoons is practicing violin in the conference room overlooking Destination Alpha, the dressy front door of the elevated South Pole Station. With the lights off to save energy and the sun behind the building from this standpoint, it feels a little like evening in the rest of the world, and I can stand looking out the window over the fuel line and down the road to the dark sector. MAPO and South Pole Telescope are out there, peering into the sky to look for information about the cosmos and galaxy clusters and how our universe was born. On weekdays there are sometimes LC-130s landing, bringing and taking away passengers and leaving us fuel for our reserve stock, humming at a high drone and accompanying my practice. It’s one of the things that reminds me, when I get distracted by the sometimes tedious workweek, to be grateful for this job and the simple fact of being here, right now.

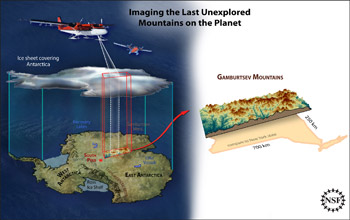

Antarctica in the News: AGAP and the Gamburtsev Mountains

Two Sundays ago, we had a Sunday Science Lecture by a scientist who works with AGAP, the Antarctic Gamburtsev Project. She mentioned that they were on the verge of a breakthrough in learning about how the Gambutsevs were formed.

Now AGAP has made international news!

You can read more about this at The National Science Foundation‘s website, on the BBC, or on the website of the US Geological Survey.

Summer Camp: You Sleep Where?

About half of the population of South Pole Station sleeps in tents. They are semi-cylindrical canvas and plywood structures called Jamesways that stand on platforms a bit off the ice and are heated with AN8 jet fuel. Summer camp is about 1/4 mile downwind from the Destination Zulu exit of the main elevated station. There are 13 or so Jamesways in summer camp that have approximately 10 rooms each, and the rooms are divided by plywood walls and/or curtains.

You can smell everyone, dirty and gassy and covered in cologne, and you can smell the history of the last 30 years of shower limitations permeating the canvas walls. Some people are lucky enough to have doors, but many people have only curtains, and you can hear every spoken word, bodily function, and footsteps of a person passing through to their room. You can hear tractors groaning up and beep beep beeping back down snow mountains outside, plowing all night long. You can hear the military planes landing on late missions, sounding like they’re so close that the wing might just clip your canvas wall and take out your pillow. Oh, and the bathrooms are a shared facility that requires going outside to get to, which can be very disconcerting if it’s 3am and the sun is shining like midday, so many people pee into water bottles or salsa jars they get from the galley. I say all of this in the fondest manner possible: I really do like living in summer camp. You can read more about the little details about living at South Pole and in Summer Camp here.

This year we are lucky–we have a double room with a door AND a latch that works, a full bed and a window. Last year when we lived in J8, we had two twin beds side by side, which was okay until you tried to roll over to snuggle and then, with a little swish, the two beds would slide apart and down you would fall into the crack. And once last year we came home to a half inch of snow on our bed(s). Not cozy. Daniel had a coworker in Jamesway 5 (J5) his first year that would get bonked on the head through his curtain every time somebody walked through with a duffel bag. Privacy is a luxury.

Over the winter season the Jamesways are closed (because who wants to sleep in a tent when the ambient temperature is -100F and the windchill is -150?) and the summer camp area drifts over with blowing ice crystals.

(Pictures by Daniel–click to enlarge)

A typical room looks like this and is about this size:

Or this:

They’ve been a part of Pole housing for a long time–decades–and they have a lot of personality. Some of them have really bad personalities, but they are interesting nonetheless.

Some of the rooms are nicely personalized, and often people will request to come back to the same room year after year.

“Attention South Pole. A Fire Emergency Has Been Reported in the Power Plant.”

On Saturday night around 7pm, just as people were settling down to their beers and cocktails, finishing dinner and showering to get ready for the summer camp dance party, a fire alarm went off. Now, fire alarms are not something we are unaccustomed to here at South Pole Station. We hold many drills and have many, many false alarms, all of which are treated as a real emergency until proved otherwise, but this was definitely not a drill, and the more we heard, the more we realized it was a genuine emergency.

“Attention South Pole Station,” said the breathless, shaky voice of the comms announcer, “a fire emergency has been reported in the power plant.” Alarms were blaring. The fire response team was suiting up in firefighting gear, donning boots and overalls and jackets and helmets and facemasks and SCBAs (self contained breathing apparatuses). First responders were already running down the stairs to the power plant arch, the trauma team was mustering in Medical, and the logistics team grouped to wait for the next instructions.

Our power plant has a carbon dioxide fire suppression system. A few seconds after the alarm goes off, the enclosed space of the plant can flood with carbon dioxide, displacing oxygen and suffocating the fire but also anyone in the plant, potentially killing them. Even a false alarm could claim a real victim. The power plant mechanic, Rick, was eating dinner in the galley between rounds, so we knew he was okay, but a utilities tech or another power plant worker (there are three—they make rounds reading levels in the plant every 2 hours, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week) could be in danger.

Those of us not on a response team sat in the galley, nervously huddled around our land mobile radios listening to the talk-around channel, hearing smoke reported first in the plant between generators three and four, then widespread. We heard the fire team yelling their next moves (they have to yell because of the facemasks), going in, checking for victims, reporting a massive glycol spill.

Comms all-called again. “Attention South Pole. We are in a power emergency. Please turn off ALL electronics not required for life and safety.”

We needed to get our power consumption down, right now. Everyone got up, trotting the halls, turning off lights and unplugging treadmills, shutting down computers and televisions and any other thing we could find a plug or switch for. The galley turned off all the stoves and refrigerators, the IT staff remotely shut down all the auxiliary servers and all of the labs. The air was quiet.

There had been a massive glycol spill as a result of a mechanical failure (a small elbow joint that had reached the end of its life). The power usage shot up to extreme levels, the peaking generator was activated, and our power plant was flooded with propylene glycol, but not carbon dioxide. The whole area was dark and hazy, like a scene from a movie where something really bad is about to happen to the protagonist. We tracked down empty open-top 55 gallon drums, absorbent pads, and every mop and mop bucket on station. An hour or two later, once the air had been ventilated and the flammable liquids and gasses had been contained and dissipated, the clearance was given and additional volunteers were called for. We suited up with earplugs and disposable latex gloves to protect ourselves from the glycol, and moved around the power plant on absorbent pads, soaking up the extremely slippery chemical on our hands and knees while someone else followed behind with a mop.

One of the best parts of living here is the active community—our emergency response team is made up of firefighters and emergency responders, of network guys and cargo women and dishwashers and mechanics and doctors and station management, all working together, and the non ERT folk were from the same mixed bag. We cleaned glycol from the floor, under nooks and crannies and fuel return pipes, from storage shelving and water tanks and generator parts, and it was awesome to see the whole station working together.

And then it was over, aside from lingering power restrictions. It was close to eleven when everything had calmed down and less than ten people remained in the plant, cleaning up loose ends and trying to determine exactly what happened. The emergency power plant did not need to be activated, and no one was hurt, not even from slipping on the glycol and falling.

And that was Saturday night at the South Pole. Sunday now leaves us happy and safe, full of brunch and coffee and sitting in rooms lit only by the 24-hour sun.

Flying from the Ross Ice Shelf to the South Pole

Flying in Antarctica tests your flexibility.

My original flight from McMurdo to South Pole was set for November first at 5 am (New Zealand time), moved forward to the 27th of October, cancelled because of weather delay, and moved to the next day, the 28th.

We took a Delta, a passenger vehicle that looks like a giant red metal ant, out to the ice runway in the morning, optimistic and excited at the weather reports for both takeoff and landing. There are two main types of delay here: weather and mechanical. We had all forgotten about mechanical delay.

Our group sat crammed in the Delta, feet going numb and legs getting stiff, blowing bubble gum bubbles that popped with a little puff of foggy breath, optimism waning with each update on the plane’s sorry status. Six hours later, tired and hungry and wishing we had landed three hours ago, we crunched and groaned and bounced along the sea ice in our Delta, returning to McMurdo for the night and hoping that there would still be beds for us despite the hundred-some people that had landed in a C-17 that day. I was disappointed but spent the evening with some girlfriends from Pole who bought me a birthday beer and told me that tomorrow was another day.

And it was. Now just three days before my scheduled flight and over a week after some other people’s, we skeptically dragged our bags back up the hill to cargo in the morning. We sat in the vehicle, comparing the food we had packed, learning a lesson from the hungry day before. Soggy sandwiches (for those who had been smart enough to pack them the day before our first scheduled flight), flat sat-upon doughnuts, granola, an avocado, or two pieces of french toast. As we progressed, we drove straight out to the runway, arrived directly at the plane (the first good sign) which was already fueled (the second good sign) and took off right on time (the third good sign).

The weather at Pole was flirting with the temperature limit that a C-130 can land in, so we crossed our fingers that our flight wouldn’t boomerang, which means exactly what it sounds like, and tried to not get too excited until we started our descent to Pole.

The flight was amazing. Laden with Emergency Cold Weather gear, boots and overalls and huge jackets and layers, you have to carefully plant each step to move about the plane and not step on or awkwardly straddle another passenger for too long. Through the tiny porthole window, and without any sense of how far up you are or how big the landscape below you is, you can see the terrain evolving below, pressing your head on the cold metal of the plane, the roaring drone of the props vibrating though your skull.

I said goodbye to dirt, watching the mountains melt into flat, blue ice like a lake surface. The face of the earth became flatter, whiter, flatter, whiter. You can see evidence of glacial flow, like seeing time pass, wrinkles and pockmarks and silky snowy spots like aged skin, shiny crusty ice that looks like you could stand on it until you shifted your weight and broke through, some marks like crop circles. Icy blue, as uninspired as that sounds. On we flew, over crevasses that look like dry, split fingertips in the winter, tiny and feathered on one side, gaping and deep and scary on the other side. I wondered if we were flying over any ski-in expeditions or what route they might take, and if they could hear us and whether they were waving at us from so far below.

(The following photos are by Marie McLane, who works cargo here at Pole and is a science tech in Greenland, and whose blog, AntarcticArctic, is pretty neat and has lots of photos and more info about flight Ops than mine so you should probably check it out.)

We landed, the engines getting louder like a volcano about to explode, and without being able to see and because of the rattle of the plane, it sometimes would seem like we had touched down even when we hadn’t. When we finally did land, I felt us turn off the skiway and onto the apron, and we droned along for what seemed like forever. The NY air national guard crew dropped the rear cargo door down, the plane yawning and flushing us with bright, bright fog and snow and steam and sucking the heat and moisture out of the plane all of a sudden. Out slid the cargo, disappearing immediately into the whiteness, and the crew closed up the door and the plane slowly crept forward and stopped.

Even though I knew what to expect this time, disembarking the aircraft was overwhelming. The ambient temperature was close to –60, the windchill nearly –90, the air was dry and the altitude was steep and the roar of the propellers just off to the side was immense and the sun was bright and here I was, returning to the South Pole, a little bit excited and pretty emotional and really really cold. I choked on my first few breaths. A crewmember held a line out from the door, to guide us and prevent passengers from getting thunderstruck and confused and turning left instead of right, walking straight into the props and losing their head, literally. All the way up to the nose of the plane came the ground crew, our friends and coworkers, putting out little guide markers showing where to walk to exit the apron.

There were cold but happy reunions with winterovers, jumps for joy and breathless hugs and frozen tears. There were new people as well as returnees with cameras and cold shutterfingers and a holy shit, I’m at the bottom of the planet stance, and, I would imagine, wide eyes behind their goggles and gaiters and balaclavas. Having arrived about a week before us, Daniel came to carry my bag for me, which seemed much heavier than it had been at sea level, and gave me a cold, wet, polarfleece little kiss.

It feels really good to be back.

More soon on the new job and life at the pole. If you’re missing blog posts and want to get more updates right to your inbox, you can subscribe for free to email or rss!

A Pickle Named Hysteria

Here at McMurdo station, Polies are starting to be ready to leave. To get going, or to go home, in a way. I’ve been learning a lot while I’m here though, trainings and briefings and orientations and meetings.

After a first night spent pretty dehydrated and dizzy, we went right to work in the morning, doing a session on operating CAT loaders: an articulated 950, a 953 and a 277 skid steer, a sweet little loader that has a safety bar like a rollercoaster and operates with a joystick. After a lot of PowerPoint slides and an informal quiz, we got to it and headed out to Willy field, a few miles off Ross Island and onto the permanent sea ice. Past giant spool parking lots, elevated fuel hose lines, piles of fine grit for making tread on ice, pickup trucks and a hazardous waste yard that was fenced off and looking like it should be guarded by an icy bulldog. Up and down a huge hill and past New Zealand’s Scott base (aptly painted kiwi green), with built up pressure ridges, huge rippled ocean waves frozen in time. Onto the ice road we drove, past radome/satellite dish protective housings, odd little eight foot spheres on sleds with red and white siding, like a giant metal beach ball or, as Ed the fuelie put it, “strange fruit of science.”

We learned about doing walkaround checks, noting glycol and engine oil levels, hydraulic fluid dribbles that needed to be scooped up off the ice, and spending quite a while shoveling, sweeping and gently ice-picking solid packed snow out of the engine compartments, air vents, and in some cases, the cab of the machine. Some of the women in the group were total pros. They didn’t need to be trained, but it was awesome to watch them work.

Finally, the vehicles started up. The 955 never made it to the driving stage, unfortunately.

We practiced going up a hill. We practiced making a K-turn on top of the little plateau. We practiced picking up concrete blocks on the forks as well as chaining them to the boom (a really different feeling, as you have a huge, heavy pendulum on the front tip of the machine). We practiced moving around an outhouse that was out by the camp (happily frozen), and marshaling the driver since the vehicle had about 30% visibility with the latrine in front of the windshield.

We spent a good amount of time sorting through, unpacking, counting and labeling South Pole food that came in on the sea vessel last season (February 2011). To be outside in the sharp wind, labeling hundreds of individual packages of fennel and cumin and coriander, hauling and hoisting huge 50-lb sacks of oats and flour, or unpacking and counting and labeling and repacking 2,000 individual pounds of butter while the wind picked up our clipboards and literally threw them in our faces, seemed a little ridiculous. And on top of it, off in the distance our backdrop was mountains with glaciers sliding out between them and this stunning, icy beauty, helicopters and C17s landing on the runway, and later the black volcanic dirt under our feet steaming in the sun, melting the ice and releasing a slow-floating mist. A strange juxtaposition of cold and uncomfortable and weird and intense and frustrating and wonderful and lovely in this special recipe that defines nearly everything we do in Antarctica.

We used a vehicle called a Pickle to unload the crates from the milvans (milvans are metal storage units the size of trailer homes). It’s a crotchety little articulated, wheeled vehicle from the Korean war era, a military specific front end loader that is no longer made anywhere in the world because the visibility is terrible, but it’s perfect for what we use it for. And its name was Hysteria.

A few days later, the group attended a sea ice and survival lecture. The sea ice safety isn’t really pertinent to those of us going to Pole, since there is no sea ice around for thousands of miles, but it was still interesting. We watched a time-lapse video of still sea ice, dynamic in nature and shifting, heaving, breathing like a living thing, which I suppose it is in a way. The survival lecture was a review; I myself haven’t taken the class, nicknamed “happy camper,” but might get to this year. In the introductions attendees were encouraged to talk about any close calls they’d had, or times they had needed to use a survival bag. One woman, from Minnesota, was caught in a storm with her team while doing research in the mountains. Winds reached 150mph and picked up and threw around 800 pound snowmobiles like toys. Of the three Scott tents the team had, all five people had to squeeze into the single tent upwind of the camp while everything else was being destroyed.

I went with a coworker on our day off to the Observation Tube, a claustrophobia-inducing steel and glasslike windowed silo buried twenty feet into the ice.

Once in the tube, with the cover shut to keep out the town din and wind and equipment and helicopter noises, it was pretty intense. You could hear the ice above you creaking softly, and seal sonar—animal clicks, slides and coos, like pressing your ear to someone else’s tummy and listening to their stomach noises, except more amplified. There were hundreds of thousands of little tiny krill with angel wings floating suspended in the water like snow, and bitty jellyfish. The mint-blue sea ice underside had frosty florets crystallized in the foreground and crept into an ombre blue-black unknown sea. it was peaceful and humbling and awesome. At one point, all the krill shot off in the same direction, and a few moments later from the opposite direction came a seal, silent, graceful, hulking, quick. Unfortunately my camera lens was frosted over by then.

McMurdo has far better scenery than Pole, but I’m ready to go, to unpack my suitcase and sleep in “my own” bed, to not feel like a transient, in the way of daily business. We’re getting a lot done here, but we’ll get more done when we get there, settle down, get in our groove. I’m excited.

How to Get to Antarctica in 11 Easy Steps

Step 1: Apply for a job.

Step 2: Get said job.

Step 3: Physically qualify (medical and dental for austral summer, plus psychological for winter). Do lots of paperwork. Actually, this is like 30 steps, but you probably don’t want to hear about them all.

Step 4: Pack, unpack, repack, take some stuff out of your luggage, repack again, and still end up taking too much.

Step 5: Go to a lot of orientations and learn about riveting things like OSHA, Information Security, payroll, health insurance, waste procedures and New Zealand BioSecurity.

Step 6: Fly. A lot. Arrive in Christchurch.

Step 6.5: Sleep off the flight.

Step 7: Go to the clothing distribution center (CDC) and try on Emergency Cold Weather gear (ECW), which has been pre-sorted and neatly lined up in giant orange duffel bags just for you: big jackets, insulated overalls, clunky boots, neck gaiters, mittens, gloves, hats, long underwear of varying weights, socks, boot liners, and more. Exchange anything that doesn’t fit.

Step 8: Enjoy Christchurch a bit, (we got to go to the Rugby World Cup Expo, and then after we got here, the New Zealand All Blacks won!), see some beautiful scenery, or pretend to, and buy anything else you need.

Step 9: The next day, put on your gear and get on the plane.

Step 10: On arrival in McMurdo, get off the plane and onto another shuttle.

Step 11: Check out beautiful MacTown!

In McMurdo! But First, a Christchurch Earthquake Damage Report

Deployment this year started with Daniel trying to find a haircut in a Denver suburb on a Sunday night, and the prospects weren’t great. The only place that was open was a men’s salon whose gimmick was hairstylists in lingerie (who were really, really interested in what you have to say. And sports). Daniel likened it to getting a burger at a strip club when all you were was hungry: a bit awkward. We flew to Christchurch without issues, other than Daniel’s flight from Denver to LAX being significantly delayed because the flight crew had to wait for the plane’s manual to be faxed to them (really). The pilot was so angry that he treated all the passengers to unlimited drinks on the short flight, courtesy of the airline, and instructed them to drink like it was Mardi Gras.

Two days later, thanks to the international date line, we arrived in Christchurch and unloaded our bags in the hotel room. Instead of succumbing to the jet lag, we walked in to the city center to check out the outside of the fenced earthquake zone. Since the February earthquake, some of the rubble had been cleared and crews in safety vests roamed the perimeter, but for the most part the city is frozen in time shortly after the quake. From what the kiwis we spoke with told us, it sounds like efforts are moving slowly and hitting red tape and bureaucratic roadblocks.

People who have been deploying with the Antarctic program for many years were affected more than the rest of us; we were staying in hotels 45 minutes out of the city center, and none of the bars, shops or landmarks that were part of their second-home city existed anymore. The streets leading up to the dead ends of fence were deserted. Creepy and quiet, without cars or people or machines or music or any kind of life other than bird noises that seemed disjointed and out of place.

It was really, really sad.

In a few places, parts of buildings had been salvaged. I asked a shuttle driver about it, and he said that a lot of the church steeples and bell towers had been removed and set aside after the first earthquake, presumably to be put on again. And then the rest of the building came down in the February quake and all that was left was the steeple.

I think the picture below is the front face of what used to be the cathedral, but it was really hard to tell and pretty far off.

Window panes hang like loose teeth.

In some places things were just slightly askew.

And in other places, massively destroyed.

We have been in McMurdo now for over a week. Daniel’s flight, supposed to be the first passenger flight in after the winter, keeps getting delayed. Every morning, the pax wake up, strip their beds, pack their bags and get ready to go, and every morning the flight gets cancelled. People are getting frustrated and missing things about Pole that are different here. More on that later.

I ‘m hoping to get a post up about life in MacTown pretty soon. The scenery here is fantastic, and there is an underwater observation tube where you can listen to the ocean and watch for sea life. So stay tuned!

Antarctica Bound 2011

After a few months of wrangling broken fax machines, drug tests, pap smears, dental fillings, mantoux screenings, turn-your-head-and-coughs, hundreds of pages of HR paperwork, many vials of blood and other costly indignities, we are on our way back to South Pole. Saying goodbye again was oddly difficult. Leaving Minneapolis was hard, and I cried on the plane after seeing downtown for the last time. I don’t even like downtown. But I am so excited to be deploying.

This is going to be a pretty special year to get to go to Pole; in December we will celebrate the centennial of Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen’s arrival at the Pole in 1911, the very first human being to EVER make it to the southernmost point of our earth. It was a battle. Robert Falcon Scott’s team, only a month behind them, made it second and subsequently died on the way home. And only a hundred years later, people like Daniel and me get to apply for decidedly non-explorer-esque jobs (IT and inventory, respectively), and go there without being even slightly worried that we are going to freeze or starve or get so dehydrated or depressed or exhausted that we die. Well, maybe a little worried, but I can assure you that’s totally irrational.

I’m also pretty excited, because Amundsen was Norwegian and I’m racially Norwegian (is that a thing? I’m going to pretend that that’s a thing). I got to visit Norway two years ago to visit relatives (hello out there!), and they, understandably, had a light-hearted and proud sense of ownership of all things Polar, but especially of the fact that a Norwegian and his team were the first humans, maybe the very first living organisms for millions of years, to arrive at the South Pole.

It’s going to be so COOL! (Get it? Get it?)