So, six weeks before we leave the ice, you may wonder exactly what I do to earn my living around here.

Everything we do at the South Pole exists solely for the purpose of supporting science endeavors. The scientists and all of their support staff need to be able to travel to the continent, eat, sleep, and research in the station and the surrounding couple of miles. Most of the science projects and subsequent departments need vehicles at some point; track loaders, snowmobiles, plow-accessorized tractors, Pisten Bullys and LMCs, Ditch Witches for trench digging, cranes, cherry-picker lifts and various other vehicles for special projects and transportation. This is where the Heavy Shop comes in. Most of these machines don’t like the regular 50 below temperatures and tend to break down often and especially need care at the beginning of the summer season after taking an 8-month nap at temperatures of 100 below.

Much of what the Heavy Shop did at the very beginning of the season was bringing up equipment for the summer. We spent a lot of time digging out herds of snowmobiles almost completely buried in winter drifts and towing them back to the shop for warmups and maintenance; towing out huge portable heaters to the heavy equipment and, after digging that out, placing the foot-wide flexible hoses of the heaters on the vehicles’ motors and covering them with old quilts and leaving them running for hours and hours just to warm them up enough for a drive back to the shop; heating up and starting shuttle vans and then pulling them off the blocks they spent the winter on so that they wouldn’t become completely buried with engines full of ice.

Now, every vehicle that comes into the shop is, understandably, completely covered with snow throughout the body of the engine, packed into the grooves of the track, iced onto the roof and sometimes even the sides. When it comes into the shop it melts everywhere, mixing with glycol, engine oil, and sometimes hydraulic fluid. Because of the rules of the Antarctic Treaty (and general common sense) this can’t just be shoveled back out onto the clean snow.

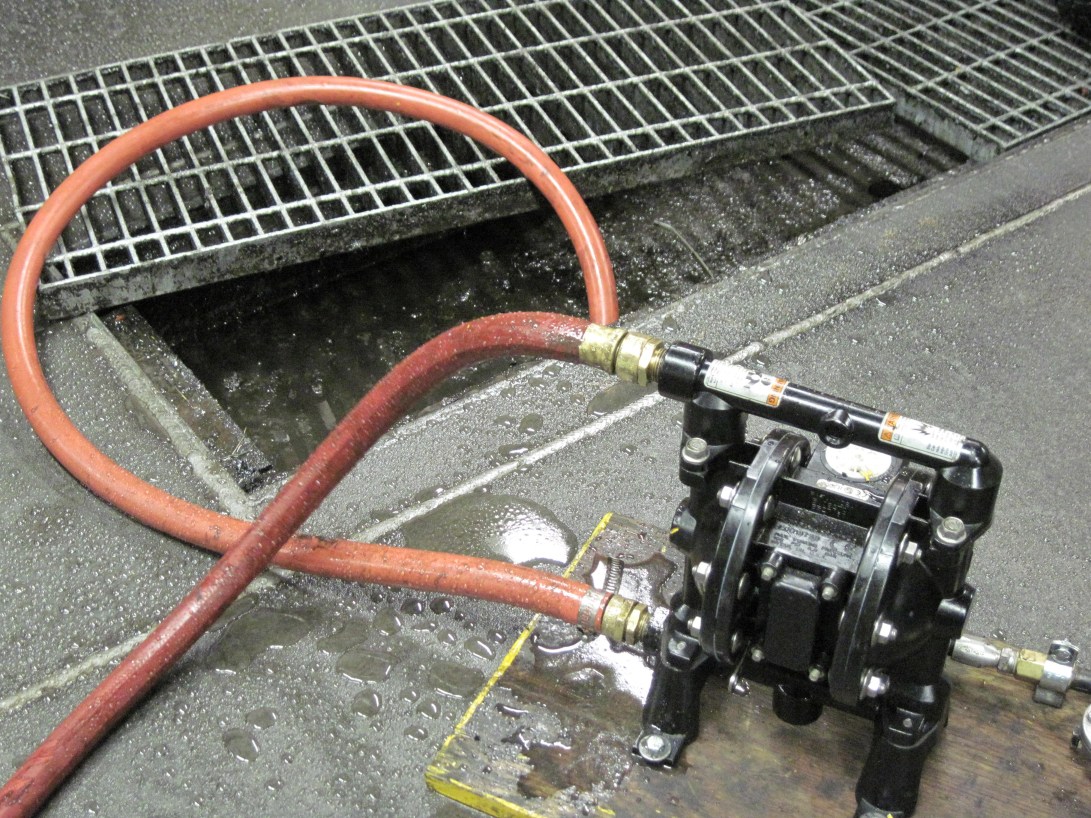

I get to remove waste ice from the shop in a variety of ways, and I spend probably two to six hours a day doing this. I can place a heating fan on the frozen grates and, when they melt to water, use a pneumatic pump to suck it out of the floor into the oil/water separator.

I can also use an air hammer, sharpened iron bar, or pickaxe (sometimes all three) to break the grate contents into smaller bits and take them out with a bucket if it’s really watery, a shovel, or by hand—pocked, sharp, oily slippery ice. If the melted water misses one of the ten or so grated reservoirs in the floor, and freezes solid to the floor, then I use the pickaxe or pointy iron bar to chop that up into small bits and sweep-shovel it off the floor. With the latter two crud-removal systems the ice has to be put into a 55-gallon drum and melted with a hot electric band. Then I get to use that same pneumatic pump to suck that waste water into the oil/water separator.

This pump (which I’ve given many nicknames that I keep to myself) tends to freeze up anytime the water running through it is too cold or slushy, when the mechanics open the bay doors to bring in a vehicle, letting 50 below air pour in (this happens all the time—it’s a shop), when it sucks up a blob of crud that blocks the suction, or when you look at it the wrong way.

Most of the rags we have are recycled torn up clothing and sheets, and once, when I put a frilly, lacy rag on the pump to keep it reasonably dry, it stopped working for almost a week out of spite; no amount of taking it apart to look for blockages, bleeding the hoses, soaking the hoses in hot water, cajoling it, or priming it with oily water could make it work again until I removed the frilly rag.

Once the water has gone through the separator, I use an electric pump to transfer it to different 55-gallon drums. Once I have two or three of these full–at the beginning of the season it was about 5 per week, but now that the temperature is up to -10 and everything is really melty, the shop is like a swamp and I do up to 4 per day–I grab it, all 440 or so pounds of it with a dolly, throw my whole weight on it, and take it for a walk. The wastewater input is through a subterranean (sub-ice-ean?) hallway that remains at 50 or 60 below no matter how warm it gets outside. I drag the now-wheeled barrel through the shop and VMF office, past the plumbers and electricians’ shop, across the Logistics Arch which houses much of the station’s frozen food storage, and over to the power plant arch. The pipe is in the naturally refrigerated hallway, but the switch to turn off the pump inside of the wastewater input pipe, which helps to prevent me from getting covered in raw sewage, is inside of the power plant bathroom, the only unisex toilet for five floors and as many departments. This is incredibly irritating because I have to wait until whoever is depositing their own sewage while reading hunting and fishing magazines is finished before I can begin my job. Once the internal pump is turned off, I remove the cap of the pipe and connect yet another pump (pump count for this task: 4) before sucking the separated waste water into the pipe to be treated.

Other things I do at work include receiving, inventorying and putting away anything we ever purchase including hoses, pumps, turbochargers, tools, o-rings, bellypans, windshields, welding materials, batteries and many more exciting objects, and anything the entire Ops department purchases (read: half the station), like amplifiers, DVDs, and sousaphones. I sweep and put things away, push water into my favorite grates and suck it out again, change the empty barrels for full barrels of ethylene glycol, arctic low-pour hydraulic fluid and engine oil, and dolly out full barrels of waste liquids and used oil and fuel filters.

I take out and sort shop trash, which is much more complicated than it sounds—everything here is recycled if possible, and the waste system is quite extensive. I’ve also gotten to do some more mechanic-y things like fixing the pump when it clogs, repairing leaky couplings on the fresh oil and glycol pumps, helping change the oil on Elephant Man, the beast of a vehicle that drags the mobile firefighting sled, and learning how to change broken fittings on hydraulic hoses. I have learned how to operate and start snowmobiles, Pisten Bullys and LMCs, and, unofficially, some of the heavier equipment like track loaders. I also get to shovel quite a bit, sometimes even for different departments which is actually pretty fun.

Despite the greasy nature of the job, I actually enjoy it. The tasks are pretty simple, just physically tiring, but it feels good to get exercise at work every day and it’s satisfying to see a task get done, even though it will get undone by the next morning. I feel really lucky to work in the VMF—the crew there is so funny and relaxed, while somehow simultaneously being some of the hardest workers on the entire station and being really responsive to the needs of the crew. My supervisors just laughed and offered advice when I overflowed the waste water barrel all over the entire shop (a HUGE mess), and later the water/oil separator (a slightly less huge mess), or when I dropped the cap to the waste input pipe through the grated floor outside the power plant, never to be seen again. I honestly think that the heavy shop is the best department at the whole South Pole, but I might be a little biased.

Thanks for letting us know the details. Interesting post and good to know about the envrionmental impact abatement, too!

With all that shovelling and ice chopping (not to mention hunting and fishing magazines, it seems like growing up in Minnesota was pretty good preparation for an Antarctic career!

Love,

Mom

I do like to read the details of your work details.

Ordinary (frozen) work is interesting.

Kip

weird question! what kind of pump is that your useing in the drains?

It was a pneumatic pump, but I don’t know the brand or origin. I suspect it was repurposed 🙂