Flying in Antarctica tests your flexibility.

My original flight from McMurdo to South Pole was set for November first at 5 am (New Zealand time), moved forward to the 27th of October, cancelled because of weather delay, and moved to the next day, the 28th.

We took a Delta, a passenger vehicle that looks like a giant red metal ant, out to the ice runway in the morning, optimistic and excited at the weather reports for both takeoff and landing. There are two main types of delay here: weather and mechanical. We had all forgotten about mechanical delay.

Our group sat crammed in the Delta, feet going numb and legs getting stiff, blowing bubble gum bubbles that popped with a little puff of foggy breath, optimism waning with each update on the plane’s sorry status. Six hours later, tired and hungry and wishing we had landed three hours ago, we crunched and groaned and bounced along the sea ice in our Delta, returning to McMurdo for the night and hoping that there would still be beds for us despite the hundred-some people that had landed in a C-17 that day. I was disappointed but spent the evening with some girlfriends from Pole who bought me a birthday beer and told me that tomorrow was another day.

And it was. Now just three days before my scheduled flight and over a week after some other people’s, we skeptically dragged our bags back up the hill to cargo in the morning. We sat in the vehicle, comparing the food we had packed, learning a lesson from the hungry day before. Soggy sandwiches (for those who had been smart enough to pack them the day before our first scheduled flight), flat sat-upon doughnuts, granola, an avocado, or two pieces of french toast. As we progressed, we drove straight out to the runway, arrived directly at the plane (the first good sign) which was already fueled (the second good sign) and took off right on time (the third good sign).

The weather at Pole was flirting with the temperature limit that a C-130 can land in, so we crossed our fingers that our flight wouldn’t boomerang, which means exactly what it sounds like, and tried to not get too excited until we started our descent to Pole.

The flight was amazing. Laden with Emergency Cold Weather gear, boots and overalls and huge jackets and layers, you have to carefully plant each step to move about the plane and not step on or awkwardly straddle another passenger for too long. Through the tiny porthole window, and without any sense of how far up you are or how big the landscape below you is, you can see the terrain evolving below, pressing your head on the cold metal of the plane, the roaring drone of the props vibrating though your skull.

I said goodbye to dirt, watching the mountains melt into flat, blue ice like a lake surface. The face of the earth became flatter, whiter, flatter, whiter. You can see evidence of glacial flow, like seeing time pass, wrinkles and pockmarks and silky snowy spots like aged skin, shiny crusty ice that looks like you could stand on it until you shifted your weight and broke through, some marks like crop circles. Icy blue, as uninspired as that sounds. On we flew, over crevasses that look like dry, split fingertips in the winter, tiny and feathered on one side, gaping and deep and scary on the other side. I wondered if we were flying over any ski-in expeditions or what route they might take, and if they could hear us and whether they were waving at us from so far below.

(The following photos are by Marie McLane, who works cargo here at Pole and is a science tech in Greenland, and whose blog, AntarcticArctic, is pretty neat and has lots of photos and more info about flight Ops than mine so you should probably check it out.)

We landed, the engines getting louder like a volcano about to explode, and without being able to see and because of the rattle of the plane, it sometimes would seem like we had touched down even when we hadn’t. When we finally did land, I felt us turn off the skiway and onto the apron, and we droned along for what seemed like forever. The NY air national guard crew dropped the rear cargo door down, the plane yawning and flushing us with bright, bright fog and snow and steam and sucking the heat and moisture out of the plane all of a sudden. Out slid the cargo, disappearing immediately into the whiteness, and the crew closed up the door and the plane slowly crept forward and stopped.

Even though I knew what to expect this time, disembarking the aircraft was overwhelming. The ambient temperature was close to –60, the windchill nearly –90, the air was dry and the altitude was steep and the roar of the propellers just off to the side was immense and the sun was bright and here I was, returning to the South Pole, a little bit excited and pretty emotional and really really cold. I choked on my first few breaths. A crewmember held a line out from the door, to guide us and prevent passengers from getting thunderstruck and confused and turning left instead of right, walking straight into the props and losing their head, literally. All the way up to the nose of the plane came the ground crew, our friends and coworkers, putting out little guide markers showing where to walk to exit the apron.

There were cold but happy reunions with winterovers, jumps for joy and breathless hugs and frozen tears. There were new people as well as returnees with cameras and cold shutterfingers and a holy shit, I’m at the bottom of the planet stance, and, I would imagine, wide eyes behind their goggles and gaiters and balaclavas. Having arrived about a week before us, Daniel came to carry my bag for me, which seemed much heavier than it had been at sea level, and gave me a cold, wet, polarfleece little kiss.

It feels really good to be back.

More soon on the new job and life at the pole. If you’re missing blog posts and want to get more updates right to your inbox, you can subscribe for free to email or rss!

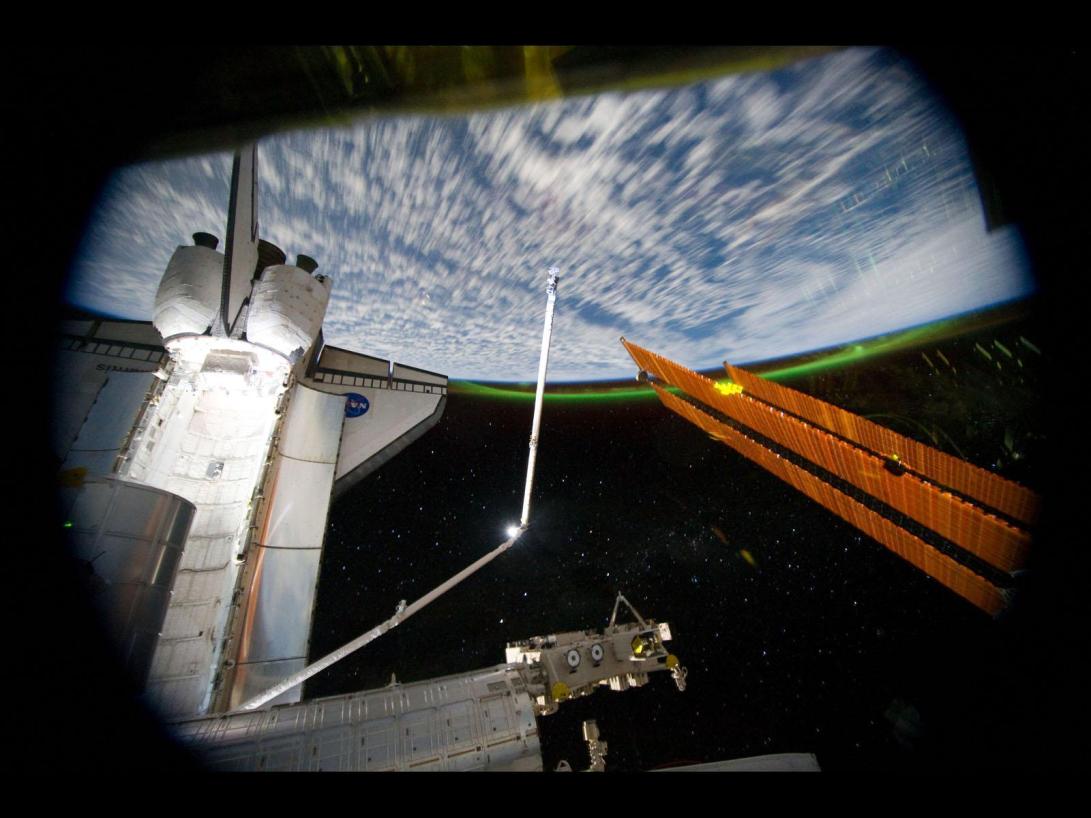

And those lovely auroras from a completely different perspective:

And those lovely auroras from a completely different perspective: